For all of the multitude of ways that Major League Baseball has changed - hello ghost runners and pitch clocks, goodbye complete games and Sunday doubleheaders - the game still has a singular hold on the American sports psyche. Its daily drumbeat of games fills up our springs and summers and falls, its timeless rhythms and traditions flowing from generation to generation. All any of us really want is for our team, our people, to get home. With midsummer, and the All-Star game, upon us, I wanted to share a story I wrote about how deeply baseball shaped our family. It appeared in the New York Daily News Sunday Magazine, 44 years ago.

Our destination was Shea Stadium, but I wasn’t sure we would ever get there. Lines of cars stretched in every direction, and we were right in the middle of them. Game 5 of the 1969 World Series, the game in which I was hoping that Jerry Koosman would put away the mighty Baltimore Orioles and elevate my beloved Mets – perennial doormats – to baseball’s summit, was only a half-hour away. Squirming with the restless energy of a 15-year-old on the brink of his first world championship, I wished hard that my grandfather could pull back on the steering wheel and lift us out of the mess. I needed reassurance.

“You think we’ll make it, Gramps?”

“It’ll be close, Joe. But I think we’ll be okay. He always called me Joe – playfully, affectionately – even though it wasn’t my name. I liked it.

We made it, and so did the Mets. Koosman was superb, pitching a complete game, and the Mets’ 150-pound mighty mite, Al Weis, hit a long homer, but my enduring memory of that day was the nasty traffic jam, and the forbearance with which my grandfather put up with it. It took us 2 ½ hours to cover the 30 miles between Huntington, L.I. and Flushing, Queens. Gramps was 75 years old. Surely there were better ways to spend his time than sitting on the Grand Central Parkway. He never let on. After the game, I’m sure he wanted to leave as soon as possible. But there was a wild celebration on the field, and Gramps knew I wanted to drink in all of it. We stayed. “Don’t get trampled,” he said. The return trip home was just as slow.

We used to go to Shea Stadium all the time, Gramps and me. I was never happier than when he took me to a ballgame, and I suspect he felt the same way. Often stern and serious-minded at home, he was downright playful during our outings. I can get to the stadium by myself now, but it’s not the same. I liked it when I’d count down the days to the big game, when I’d stand fidgeting by the front door, lefty glove in hand, waiting for Gramps to wheel into the driveway. Adulthood has made going to the ballpark much too easy.

The heralded New York homecoming of the Giants in 1962 was the first game he ever took me to. I was too young and too awed by the bright lights, crisp uniforms and vast, verdant expanse of the Polo Grounds outfield to appreciate the drama of the occasion, though not so young or awed to forget that the Giants had an all-Alou outfield (Matt, Felipe and Jesus) that night. Hindsight presses the memories together now, of that game and all the rest, because our times together always were the same – special and warm. There was the rush of riding in Gramps’ big. blue Oldsmobile, a cavernous car with a multi-colored speedometer, which I eyed with fascination as it changed from green to yellow to red as we accelerated; the bologna sandwiches and Cracker Jacks and Fig Newtons from Grandma; the nonstop chatter about batting averages, home runs and pennant races; and the unstated joy of two people, 60 years apart, sharing a love for a game and each other.

There was also the contrived argument about when to leave. Almost without fail, come the sixth inning, Gramps would begin gathering his things and start to stand up. “C’mon, Joe, it’s time to go,” he’d say with a woeful excuse for a straight face. “We’ll catch the end on the radio.” The first few times, I panicked.

“Whatdya mean, Gramps? The game is barely half over!” He tried to persist, but his smile always betrayed him. We never left early. Even if the score was 10-1 in the second game of a twi-night doubleheader, we stayed to the end. Traffic jams, fatigue, inconvenience – it all paled next to his grandson being happy. I appreciated it then, and even more now.

Gramps knew just what to say and do to make our ballpark trips the best. He let me be a kid. I chased after autographs before the game, and foul balls during it. I cheered, booed, kept score, and stalked hot dog and soda vendors every few innings. Gramps paid for all of it.

“If you get a stomachache, your mother ain’t never going to forgive me,” he’d say.

I remember the first time he let me go to the concession stand by myself. For two innings, I wallowed anonymously on an imprecise line, watching a jostling stream of much larger bodies come and go. I was close to tears, not because I couldn’t get my pound cake, but because I felt so lost and inconsequential. Despair had just about prevailed over hunger when I felt a large hand on my shoulder. My grandfather was a steamfitter by trade. His hands were strong. On the concession line at Shea Stadium, they felt gentle.

“Guess you’re not having too much luck, Joe, huh?”

He shepherded me to the front of the line. At the counter, he lifted me up so I could place my pound cake order. We walked back to our seats hand in hand.

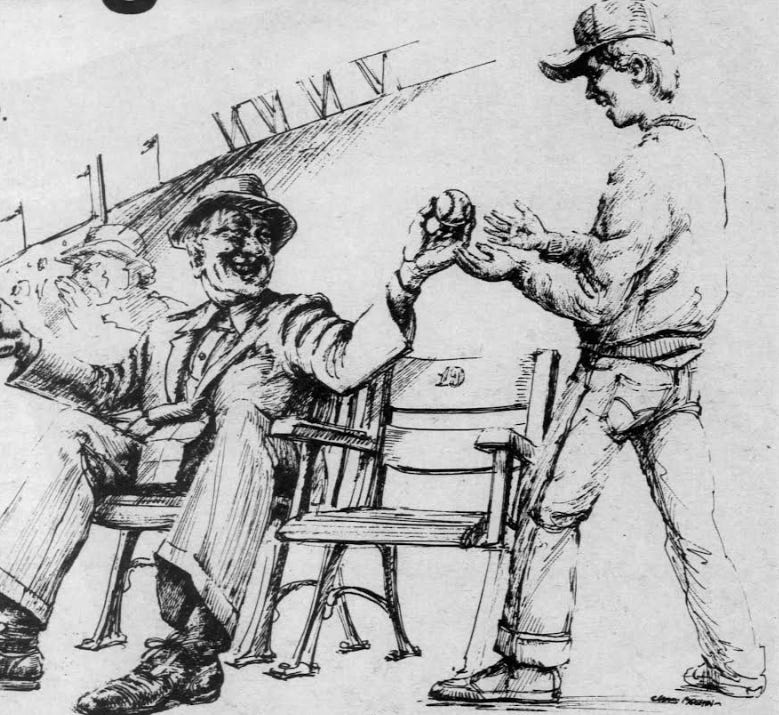

World Series Game 5 notwithstanding, we always made a point to get to the park early, to take in batting practice. One time it really paid off. Returning from a hot-dog hunt, I scanned the box seats behind first base for Gramps. Just as I spotted him, an errant throw from the outfield skipped neatly on one hop, right into his lap. Dumbfounded, I sprinted to our seats. Gramps was grinning in a way I’d never seen before.

“Look what your ol’ Grandpa got, Joe,” he said, handing me the ball. I still have it.

Gramps and I talked about baseball incessantly. Mostly, I talked and he listened. He followed the game avidly for half a century, but seemed to get the biggest charge hearing me recite statistics about Ron Hunt and Frank Thomas and many others I’d memorized from my baseball cards. When he did talk, it was usually in attempt – almost always successful – to get me riled. He knew the button to push was Mickey Mantle. The Mick, as I called him, wasn’t just a baseball idol; he was virtually my raison d’etre until the day he retired. When we watched Yankee games on TV and Mick would stride to the plate, the famous No. 7 on his impossibly broad back, Gramps would look at me and say, “Here comes another strikeout.”

“Oh yeah! You’ll see. C’mon, Mickey, knock one outta here!” It didn’t really matter what Mick did.

*

The years raced by. It was the middle of another baseball season when I laid awake one night, wondering if it had really been nine years since I’d been to a ballgame with Gramps. College, career, moving away for my first job and Gramps reaching into his mid 80s – they all conspired against us. We were as close as ever when we got together for holidays or special family occasions. No matter the season, we always managed to get in some talk about the Mets or the Yankees or that year’s free agent class or whatever came up. Baseball remained a special bond between us, one that connected two lives heading in different directions. I decided that before any more time slipped away, we needed to go to another game together. Only this time, I would be taking him.

“Hey Gramps, the Giants are in town next week. What do you say we get tickets for one of the games?” I said. He was taken aback.

“Oh, I don’t know, Joe. It’s been a long time since I’ve been to the ballpark. You better go ahead without me.”

“C’mon, Gramps. It’ll be great. It’s a day game in the middle of the week. It won’t be too crowded. We won’t get home late. It’ll be fun, just like always.”

He looked at me with a wry smile, his blue eyes illuminating his whole face. “You sure you wanna be stuck with your ol’ Grandpa?”

“Get off it,” I said. “Just as much as you wanna be stuck with your grandson.”

In many respects, I was wrong; it wasn’t just like always. Gramps had trouble following the action. His mind was right there and he knew the players as well as ever. The problem was his eyes, which couldn’t keep pace with the movements on the field. He seemed distracted much of the time, perhaps by his physical limitations, perhaps by the constant buzzing of the park around us. One time, on a close play at the plate, I looked over at him. He was staring out at the outfield.

It might have been sad for me, but it wasn’t, because I knew Gramps was happy to be there. For him, it was enough just to be together, to be invited to one insignificant game. We talked and joked and ate Grandma’s packed lunch, and I told him after I bought him a couple of beers, “You better not come home drunk, or I’ll never hear the end of it from Gram.”

Gram said that Gramps talked about our day together for months. It meant the world to him, he told her, and that touched me deeply. Almost enough to dispel the guilt I felt for not having taken him much sooner, and much more often.

Gramps didn’t make it to see another baseball season. The emptiness, the gaping void he left behind, lingers still. Whenever it threatens to overwhelm me, I turn to the crack of the bat, a sunny summer day, Mickey Mantle and the name Joe. Most of all, though, I turn to the memory of our last game. It was the best one of all.

These memories were so special for me to read. Beautifully written Wayne.

I envy your relationship with Pop. Not only did you have different names for our grandparents, but you had a special, very personal relationship. Thanks for sharing.