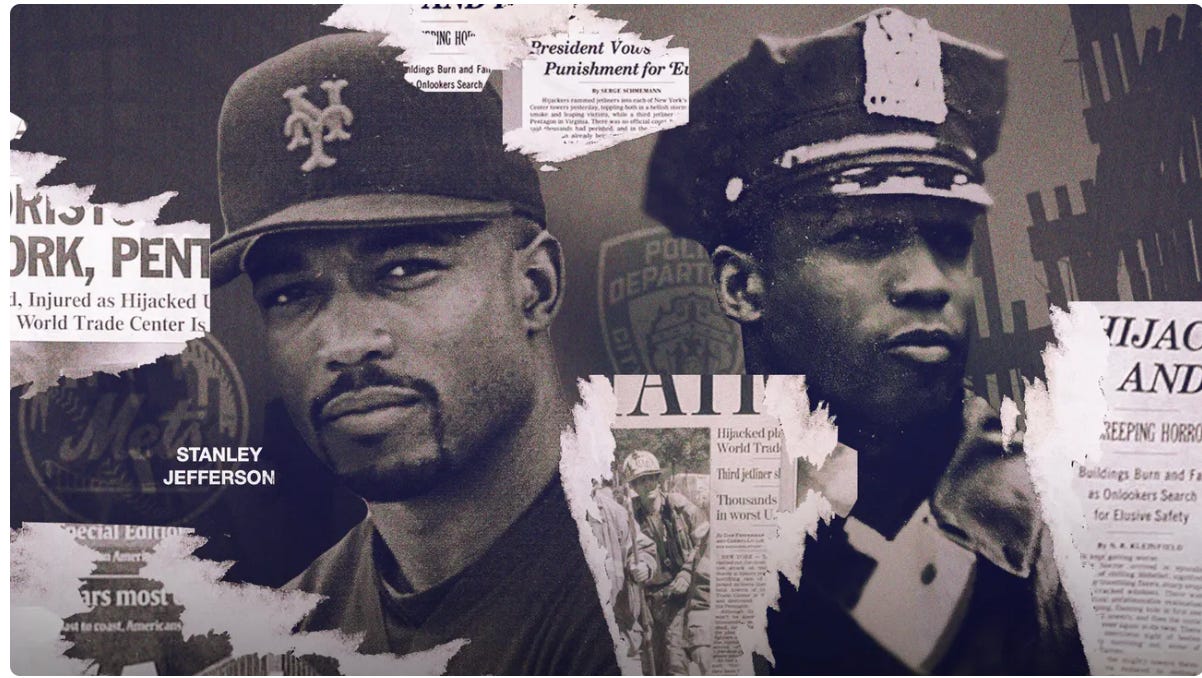

Never Forget

Stanley Jefferson, a former big-league ballplayer, went on to fulfill a lifelong dream by becoming a NYC cop. He was on duty on Sept. 11, 2001. His life has never been the same.

Not long after daybreak this morning, on the 24th anniversary of the most traumatic day of his life, a once-heralded major-league ballplayer planned to arrive at Crandon Golf course in Key Biscayne. He would play the round the way he almost always does, the way he prefers – by himself. Golf may be the most sociable of games for most people, full of banter and bonhomie, but it’s not that way for Stanley Jefferson. Nothing is. He lives alone and golfs alone and goes for his long walks by the ocean alone, iPods in place, audiobooks on play. He talks regularly with his longtime friend, Steve Brandstetter – like Jefferson, a New York transplant in south Florida - and almost nobody else.

“I’m trying to hide,” Jefferson says. “When I go for my walks, it’s just me and the squirrels and the iguanas.” He pauses and laughs, a deep, robust laugh that you don’t quite expect from a man who has endured, and seen, the pain and suffering Jefferson has. Maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise that he isn’t feeling reflective just because the calendar today says September 11.

“Most of the time I don’t even know what day it is,” Jefferson says.

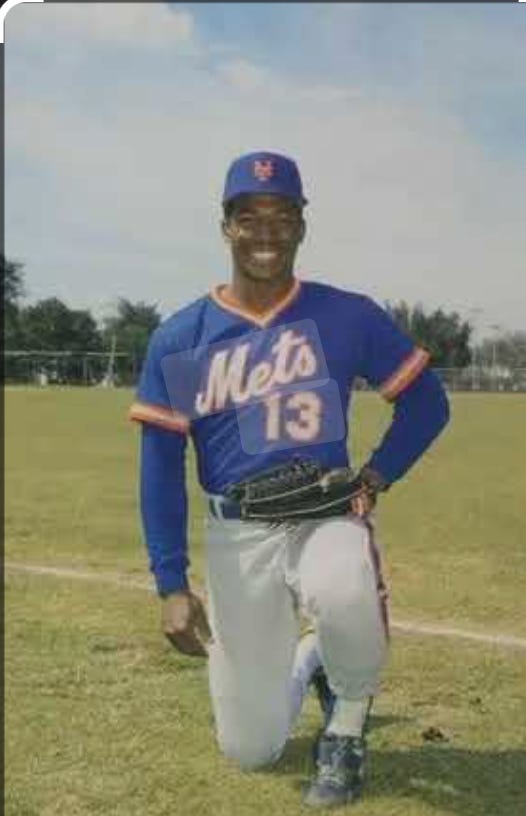

Stanley Jefferson, 62, was one of the most gifted schoolboy athletes ever to come out of New York City. A first-round pick by the New York Mets in the 1983 MLB draft, the 5-foot-11, 175-pound Jefferson starred at Truman High School in the Bronx and then at Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, Fla., where he stole 67 bases in 68 attempts. He had ropes of muscles and sprinter’s legs, and at his Mets tryout, he covered 40 yards in 4.27 seconds – almost certainly making him the fastest player the club has ever had. In one Bethune-Cookman game, Jefferson, a righthanded hitter (the Mets would later try to convert him to a switch-hitter to take advantage of his speed), beat out a two-hopper to first base.

Willie Daniels was a teammate of Jefferson’s in both high school and college. “I played with Devon White, Shawon Dunston, Walt Weiss, a lot of guys. Stanley is one of the best pure athletes I’ve ever seen,” Daniels says.

Jefferson advanced quickly through the Mets’ farm system and seven months before Mookie Wilson and Bill Buckner would become forever linked in World Series lore, he was a spring-training sensation in 1986. “How can you not love his future?” Rusty Staub said. Joe McIlvaine, then the assistant GM, envisioned Jefferson playing for years alongside Darryl Strawberry in the Mets’ outfield.

“If the ball is in the ballpark, Stanley Jefferson will catch it,” McIlvaine said.

Jefferson got his first call-up to the majors in September 1986, but he never had more than a cameo in Flushing. That winter the Mets traded for the Padres’ Kevin McReynolds. The Padres insisted Jefferson be included in the deal. Jefferson saw the trade as a fresh start, a chance to get away from the pressure of being a hot prospect in his hometown, and he had his moments, stealing 34 bases, hitting eight homers and seven triples in 116 games. But he had a string of injuries, slumped at the end of the season and had a bumpy relationship with Larry Bowa, the Padres’ volatile, hard-driving manager. Jefferson played in only 49 games the following year, and by 1989, he was traded to the Yankees and then the Orioles. His six-year career ended when he tore his Achilles tendon playing winter ball in Puerto Rico in 1991.

“Physically, athletically, I had all the tools, but I didn’t live up to those lofty expectations,” Jefferson says.

He took a few baseball coaching jobs and worked as a warehouse manager for a time, but then he pursued a long-held dream of becoming a New York City police officer. He enrolled in the academy and went through a battery of tests, both physical and psychological. “He was the perfect package for what you look for in a police officer,” one of his academy instructors said.

In the spring of 1988, he graduated from the academy and was welcomed to the force by mayor Rudy Giuliani.

The Mets’ former No. 13 was now NYPD shield number 14299. He was assigned to the Midtown South precinct, and for three-plus years life as a police officer was all he hoped it would be. He reported to work a few minutes after 7 a.m. on September 11, 2001, having flown all night on a redeye after attending a family wedding in Seattle. It was a dazzlingly beautiful late-summer morning. Jefferson and his partner, Ed Kinloch, were eating breakfast in their squad car at the corner of 6th Ave. and 38th St. It was 8:45 a.m. A minute later, an urgent message came over the radio saying there had been an explosion at the World Trade Center. There was no inkling at that point that it had been a terrorist attack. Jefferson and Kinloch were told to go to Union Square at 14th St. As they drove downtown, Jefferson got a glimpse of the remains of the first tower, taking in a scene he will never forget, people jumping from the building into the most smoke he’d ever seen in his life. He was still trying to process that when he watched a second airplane fly into the other tower. There was a massive fireball and the deafening sound of total destruction. All of lower Manhattan was shrouded in smoke. Amid the chaos, people were hugging and crying, trying to make sense of the incomprehensible. Jefferson and Kinloch did all they could to comfort people and direct them and answer whatever questions they had. They worked until 9 p.m. that night and were back at it at 4 a.m. on the 12th, before being assigned Ground Zero all day Thursday and Friday, 12-hour shifts that entailed working on the pile, on the bucket brigade, stuffing body parts into bags, the carnage seeming to have no end, the beeping of the empty oxygen packs of departed firefighters a shrill symphony that never stopped. Most of the packs had flesh attached to them. The rescue crews were told to put them in a makeshift tent.

“It was the smell of death in there, a smell you never forget,” Kinloch said later.

Jefferson worked more shifts at Ground Zero in the ensuing weeks. Every one of them was awful but he had a job to do and he did it. It wasn’t long before he developed a persistent cough and recurring nightmares. It was just the beginning. His heart would race and panic attacks would overcome him with no notice. His depression and anxiety were constant. He was diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and it didn’t help at all when the NYPD fought his efforts to get a disability benefit that would amount to 75% of his salary, the department contending that many of Jefferson’s mental-health challenges were pre-existing and not caused by his time at Ground Zero.

Jefferson’s panic attacks made him a regular at emergency rooms in area hospitals. One of the worst came when he was driving from his home in the Bronx to an administrative hearing. Suddenly his eyes became blurry, and he started to sweat profusely, his heart beating with jackhammer force. He went to the ER at Lenox Hill. He wondered if he was losing his mind, or having a nervous breakdown, or both, and had no idea how it was going to end. He pleaded with his superiors – and so did his therapist – to shift him to an administrative position until he got better. The pleas got nowhere.

A fellow officer, a sergeant, wrote a letter in support of Jefferson to the department’s medical board. “No consideration for his predicament was afforded him,” the officer wrote, adding that the culture of the department was to make anyone who is incapacitated feel like an outcast. “Most will doubt the veracity of your illness and compassion is out of the question.”

Not even 48 hours after being discharged from Lenox Hill, Jefferson, of his own volition, scheduled an evaluation with the NYPD’s Psychological Evaluation Unit. It lasted two hours. Jefferson was accompanied by his then-wife, Christie. He was deemed unfit for police work and his handgun was taken from him.

It took years, but Jefferson finally was able to get his full 75% benefit. It made things much more manageable financially. It didn’t take away his panic attacks, though, or the agoraphobia that at times has made him feel like a prisoner in his own life.

Jefferson moved to Miami about 10 years ago, and the sun and warmth have improved his outlook. So has being near the ocean. He says he still has more bad days than good, but overall is in a better place. His two grown daughters live in Virginia, and so do his three grandchildren. He’ll travel to see them once or twice a year. He’ll play his golf and go for his walks. He enjoys watching sports on TV, and listening to his audiobooks.

“I’m not as much of a hermit as I was in New York,” Jefferson says, with another of those deep laughs.

Steve Brandstetter believes his friend has developed a sharp understanding of situations and activities that might trigger a panic attack. Jefferson doesn’t watch the news and wants no part of TV shows or films that involve violence, police chases or any sort of calamity. When he is out in a public place, he makes sure he has a wall or building behind him, or even a post.

“He doesn’t want to be blindsided,” Brandstetter says. “He wants to do things, but new environments can throw him off. Stanley still has (his challenges), but overall I think he’s doing amazing.”

Brandstetter has recently started a philanthropic organization called “Celebrate Life.” He was thrilled when Stanley agreed to join the board of directors. They discuss new initiatives and fund-raising ideas, different ways to make life better for those in need.

“Stanley is a wonderful man,” Brandstetter says. “He’s not my friend. He’s my brother.”

Stanley Jefferson’s father spent a lifetime volunteering and mentoring kids in their Co-Op City neighborhood. He saw the impact his father had on people’s lives. Now he can do the same.

“I’ve always wanted to help people,” Jefferson says. “My issues have hindered me, but this helps.”

The perfect day for this powerful story. So glad to hear Stanley has found some peace. He deserves it. He earned it.

Sad and wonderful...a good reminder for us all....