He was kind. He was humble. He was the Last Boy of Summer. A Salute to Carl Erskine

Two years ago, when Gil Hodges finally made it to the Baseball Hall of Fame on his 35th time on the ballot, Craig Muder, the Hall’s communications director, asked me to write a piece about him for the Hall of Fame Yearbook. I had just finished a book on Hodges’ 1969 Mets (https://www.amazon.com/they-said-couldnt-be-done-Books/s?k=they+said+it+couldn%27t+be+done&rh=n%3A283155 “They Said It Couldn’t Be Done), the most wondrous sporting event of my childhood, and was honored to say yes.

The first phone call I made was to Carl Erskine, Hodges’ only surviving teammate from the so-called Boys of Summer, the fabled Brooklyn Dodger clubs of the 1950s, who were beautifully memorialized in Roger Kahn’s book of the same name. Carl and I had spoken a few times before and it was always a treat because he was smart and funny and had a memory like a vault. This conversation was no different, Erskine recounting how Hodges, an immensely strong man, took it upon himself to protect Jackie Robinson, who was a frequent target of taunts and cheap shots by the Neanderthals who didn’t appreciate a man of color integrating their game.

“There were a lot of plays at second where something was about to erupt, but then Gil would run down there and calm everything down,” Carl told me. “Once Gil arrived that was it. You could call him the peacemaker.”

In my entirely subjective estimation, Carl Erskine was one of the best people ever to grace a big-league ballfield. A top-tier pitcher, 20-game winner and a World Series recordholder, he became a champion when the Dodgers beat the Yankees in the 1955 World Series, but in truth was a champion of humanity for the entire span of his long and big-hearted life.

Erskine was born 97 years ago in Anderson, Indiana, a small city 40 miles northeast of Indianapolis, and died of pneumonia in Anderson Community Hospital earlier this week. In 2022, Filmmaker Ted Green made a documentary about Erskine called “The Best We’ve Got: The Carl Erskine Story.” The title came from a quote Green got in an interview with former Indiana governor Mitch Daniels.

“You didn’t have to be a lifelong Dodger fan to be a huge fan of Carl Erskine and the remarkable character with which he led his life,” Daniels said in a statement to the IndyStar two days ago.

Arm injuries ended Erskine’s career at age 32, just one season after he won the first game the Dodgers ever played in Los Angeles, before almost 79, 000 fans in the Coliseum. He packed a lot into 11 years. He pitched in five World Series and struck out a then-record 14 Yankees in Game 3 of the 1953 Series, including Mickey Mantle four times. In 1956, he threw his second no-hitter, the first one in baseball history to be on national television. At 5-feet, 10-inches and 165 pounds, Erskine was far from the biggest Dodger, but he threw hard and his big-breaking overhand curveball was his signature. So was his nickname – Oisk, as pronounced in classic Brooklynese.

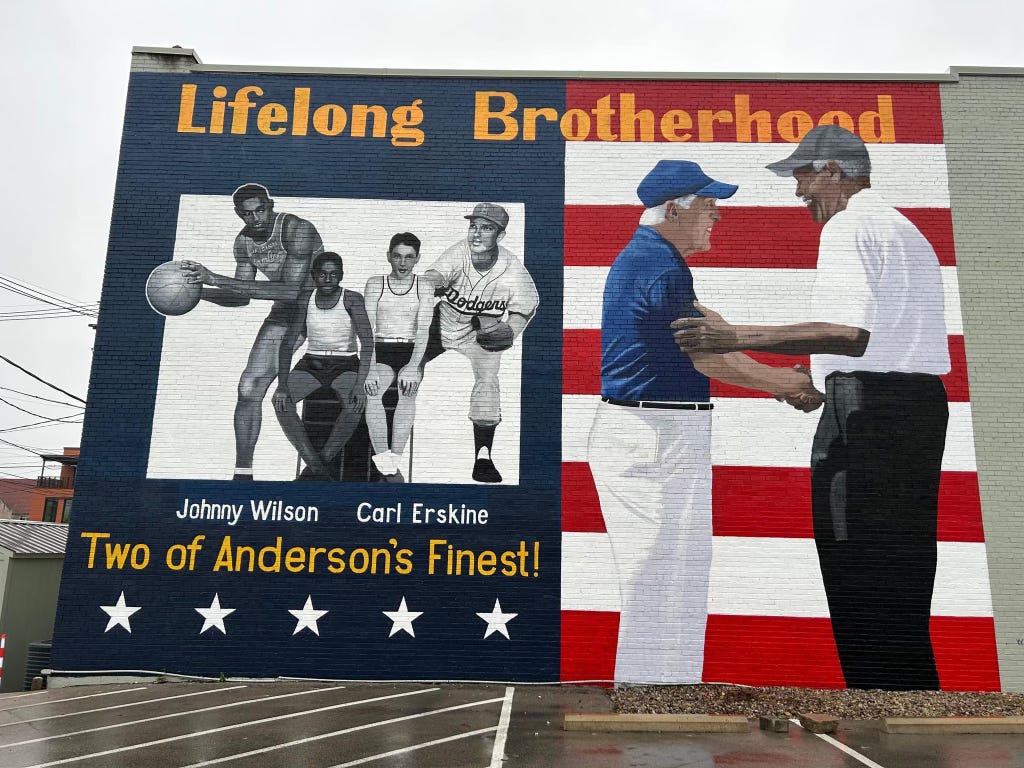

Long before he achieved fame in Brooklyn, Erskine was a standout baseball and basketball player at Anderson High School. In basketball, he and “Jumpin” Johnny Wilson, the team’s best player, led Anderson to the semifinals of the Indiana state tournament in 1944. Erskine and Wilson, an African-American, had been almost inseparable from the time they met as youngsters on a basketball court. The Ku Klux Klan was an active presence in Indiana in that time, and segregation was the societal norm. Erskine refused to play along. Johnny Wilson was one of his best buddies and everything else was irrelevant. It was no different when Erskine joined the Dodgers and became friends with Jackie Robinson. Wilson likely would’ve attended Indiana University, but the school did not accept Black students, so he wound up playing for the Harlem Globetrotters. Wilson and Erskine remained close the rest of their lives. On the side of a building in downtown Anderson, a new mural depicting Wilson in his Globetrotters uniform and Erskine in his Dodgers uniform, side by side, will be dedicated next month.

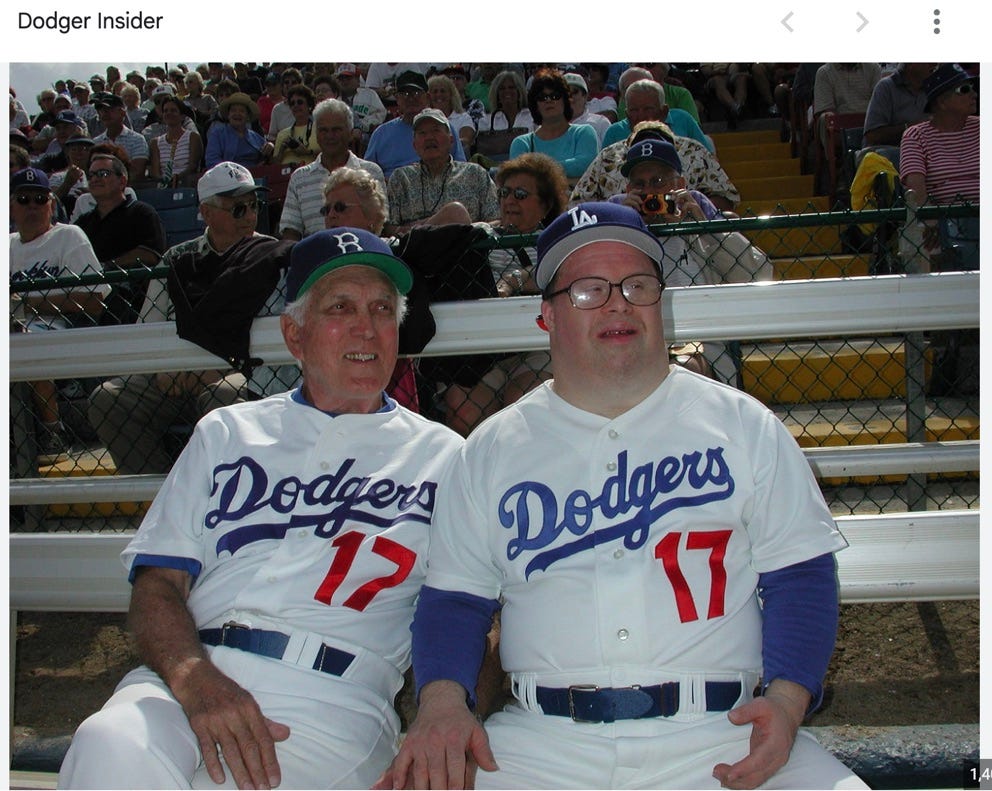

Erskine and his wife of 76 years, Betty, raised four children. The youngest of them was Jimmy, who was born in 1960 with Down syndrome. Here, too, the Erskines refused to adhere to societal attitudes, which at the time called for children with Down syndrome to be institutionalized, effectively cast aside so nobody would have to see them or deal with the challenges they presented. Jimmy lived at home with his parents and siblings. He was nurtured and loved.

At age ten, he began competing in Special Olympics and it was one of his favorite things to do, his parents becoming tireless advocates for acceptance and inclusion, lauded by Special Olympics Indiana for having an “immeasurable impact” on its mission. Jimmy got a job at Applebee’s and kept it for decades,. His father drove him to work most every day. Jimmy loved drumsticks; his father was constantly buying him new ones. Sixty years ago, it was uncommon for Down syndrome children to live much beyond 10 or 15 years. Jimmy Erskine died last November. He was 63 years old.

Often when he was asked to give a speech and talk about being a star ballplayer and champion, Erskine would show the audience his World Series ring. Then he would reach into his pocket and hold up one of Jimmy’s gold medals from the Special Olympics.

"You tell me, which is the greater achievement? " Erskine would say. Last summer, Erskine was honored by the Hall of Fame with the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award, in recognition of his contributions to society and for enhancing baseball’s impact far beyond the diamond. A dozen years ago, Erskine wrote a slender book called The Parallel, about the similar challenges that Jackie Robinson and Jimmy Erskine faced in their fights against discrimination, prejudice and misunderstanding.

“Carl was very, very proud of Jimmy,” Jim Denny said.

Denny has been an Anderson firefighter for 27 years, with a lawn-mowing business on the side. In recent years has been as close to Erskine as anyone. He will be a pallbearer at Erskine’s funeral on Monday. Denny considers it one of the greatest honors of his life.

“Carl just had a way about him that makes you want to love him,” Denny said. “He’d do anything for you.”

What a wonderful tribute to an especially wonderful man. Beautifully done.